In gratitude for the love we are to receive

I love pecan pie. Yesterday, our realtor gifted his clients with Thanksgiving pies. We bought our house two years ago, in the middle of a crazy market, when investors were slinging cash like the Monopoly banker. Without his expertise, we wouldn’t have been able to find a place to call home. For that, we are grateful to Kreg Hall. The pie is a bonus. A large bonus, as I am the only one in our household who likes or can eat pecan pie. To make it last, I’ll freeze portions and enjoy it during the winter months. Each time I sit down with coffee and a slice of pecan pie, warm from the microwave, I’ll lift a fork in gratitude for the blessings we have and the good people in our life.

Below is a post from 2017. I wanted to share it again, I hope you enjoy reading it.

Join Hands, Give Thanks

I lived through two decades before I discovered that there were people in the world who made dressing with stale bread cubes instead of fresh cornbread. My oldest sister’s second husband, the nice one, was from somewhere up North. New York, I think. He had dark, pomaded hair swept up and back and he smiled and spoke with an accent I had only ever heard on television. He made a bread stuffing with oysters. I forgave him because it was delicious, each mouthful a feast of earthy black pepper mixed with the salty ocean taste of oysters. Home from college, my mother volunteered me to drive the two of us up to Malakoff, Texas, where my sister and her new husband had retired to life by the lake. In those days before GPS, I got lost following my sister’s handwritten directions. We arrived late, but to a feast still warm and laid out on their Formica topped kitchen island. I wish I had asked him for the recipe for that oyster dressing.

My mother made her dish the Southern way, with cornbread. She used white corn meal, soft as sand, with a bit of flour, scooped up and sprinkled in like snow. Baking soda and baking powder for leavening, for we all need incentive to rise. Buttermilk to mix, salt and bacon drippings for flavor, then all poured into her largest cast iron skillet, warmed on the stove so the crust will brown first. It came out like a pale yellow moon and filled the kitchen with the warm, sweet scent of corn. For the dressing she mixed in celery, onions, broth, and enough sage to repel evil spirits.

When I was young, we traveled to my grandmother’s house for Thanksgiving. Not over the river or through the woods, but past the lake and along Highway 380 the 15 miles to the town of Farmersville. My mother brought her cornbread dressing and a pie or two as her contribution to the meal. I held the warm pan of dressing on my lap where I sat in the slick vinyl backseat of our 1970 Oldsmobile and tried not to drool on the foil covering the pan. My grandmother’s wood frame house had a tiny living room decorated with an autographed photograph of a famous televangelist, before the fall. She sent him money and prayed for healing by laying her hands on her Chroma color television while he preached. The children, including anyone under the age of 18, were banished to the back porch. We fought over metal folding chairs and balanced our plates of food on our knees while we fended off the horde of feral cats living in my grandmother’s yard. The cats were only slightly outnumbered by my cousins.

Some years we visited my father’s family, where my aunts made their dressing and gravy seasoned with the chunks of turkey heart, liver, and gizzard that came packaged and concealed inside a store bought turkey. The first time I cooked a turkey I didn’t realize there was this hidden prize inside. I found them after, steamed and tucked under the skin at the front of the turkey, where his neck would have been if it weren’t shoved up into the body cavity. The neck was roasted too, because I didn’t know there was a second, secret scrap part buried inside my turkey.

My first husband was from Missouri, and the bread stuffing his mother made was moist, but thick, and had to be scooped out in chunks. My father-in-law, an honest, hard-working mechanic and assistant Boy Scout leader, led the prayer each year, insisting that we all stand before the table and join hands. You haven’t really experienced Thanksgiving gratitude until you’ve had to convince a squirming toddler to stay still during a ten minute blessing while the aroma of roasted meat and cinnamon spiced pumpkin wafts over you in a moist cloud of steam you can taste.

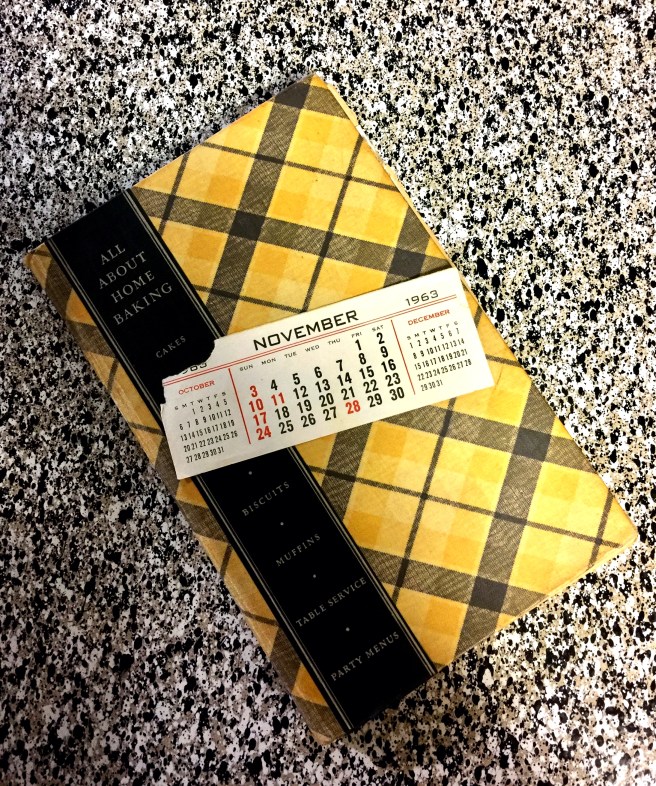

My mother stopped cooking a turkey for Thanksgiving after my parents divorced, when it was just the two of us left at home. She would roast a chicken instead, and make her cornbread dressing. I never saw her consult a cookbook. She cooked from memory, measuring out ingredients to taste except when she was making a pie or a cake. After she moved into a nursing home, I found a cookbook tucked away in a box she had stored in her laundry room. The book, All About Home Baking, had penciled notes in the margins and tucked inside the front cover, scraps of lined paper with recipes written in her delicate, looping cursive. Brittle, yellowed pages from a 1963 calendar fluttered out like falling leaves when I turned the pages of the book.

I roast a turkey every year, even when there are just one or two guests and my vegetarian husband at the table. This year I’m cooking both turkey and a ham. I’ll make cranberry relish from fresh cranberries and oranges and add so much sugar that it passes for jam. We’ll have pumpkin pie and a minced meat pie like my mother used to make, even though no one but me will eat it. It is a deliberate luxury on my part to have a whole pie to myself. My husband, Andrew, will mash potatoes so they come out just the way he likes them, a little bit creamy and with a few tiny lumps. When he leaves the kitchen I will sneak in more butter and salt to the dish.

I don’t cook my mother’s cornbread dressing. I’ve fallen from grace and into the boxed, instant variety but at least it’s the cornbread version. I’ll make traditional green bean casserole with crispy fried onions on top and a spinach rice casserole from a recipe my aunt gave to me. I don’t put marshmallows on the yams, instead I’ll serve them with a pecan streusel topping like my ex-husband’s mother, my first mother-in-law, made.

The guests at the table, the cooks in the kitchen, and the fellowship changes, just as the feast stays the same. I touch my past as my hand stirs the pot, preps the bird, and kneads the bread. I bow my head in silent thanks and join hands with all, even those who are absent from the table. Join hands, bow heads and give thanks. Give thanks for the love we are all about to receive.